Written by Shawana Brooks, Guest Contributor

Amid concrete ripped apart where 2nd Street used to be whole sits the Moneyhun residence. An orange cone and debris are the new markers. Construction has annihilated the roadway for over six months, making the view out of the kitchen less than optimal for this beachfront residence. This has made getting to the front door a sandier walk than usual. But no complaints were made by me trekking two blocks in kitten heels. Who wouldn’t be excited to come to see Hiromi Moneyhun’s home studio? Most people were quite envious when told where I was headed. It is where the magic indeed happens.

Amid concrete ripped apart where 2nd Street used to be whole sits the Moneyhun residence. An orange cone and debris are the new markers. Construction has annihilated the roadway for over six months, making the view out of the kitchen less than optimal for this beachfront residence. This has made getting to the front door a sandier walk than usual. But no complaints were made by me trekking two blocks in kitten heels. Who wouldn’t be excited to come to see Hiromi Moneyhun’s home studio? Most people were quite envious when told where I was headed. It is where the magic indeed happens.

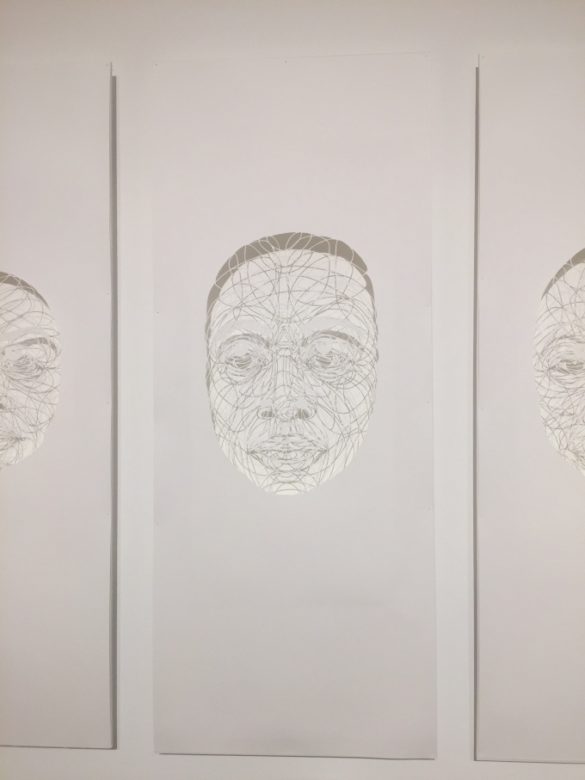

Beautiful wood grain with Japanese-influenced architecture is the home’s décor. Minimal but optimal. Though she hasn’t been exhibiting very long (her debut was in 2012), the art community is falling over Hiromi’s work. Her paper-cuts are so complex and delicate, and simply breathtaking, that they defy the madness of the long hours required to execute them. The work feels a bit mystical and magical, perfection in every slice. The viewer cannot stare without wondering how she accomplished this fragility. It is noteworthy to realize that she did not start out with paper as her medium. Hiromi’s career as an artist is evolutionary. I say her skills are to be reckoned with, a master among us. But Hiromi would refuse such a compliment. “Thank you and I appreciate it, but no,” she says. An imagined ingénue and an enigma.

Take It From Me, Countries Just Don’t Understand

Hiromi is non-binary. This means she doesn’t identify as male or female. She is completely and absolutely, Hiromi. This can cause confusion to articulate the language of our ever-changing identity landscape of Americana. True, she is married and has had a child but labels can’t contain her individuality or identity.

“I am just Hiromi.”

As a transplant, Hiromi has had her own issues with language and interpretation. English is her second language, and at times her husband, Roy Moneyhun, will make sure her point is clearly stated. And if she does take a little more time to mull over her translations, that is because America is not always tolerant to those with a foreign accent. She recalls an incident of trying to communicate with a cashier who was unreasonably upset and frustrated from her speech. It was one of her first experiences living here.

She left Japan, and Jacksonville was her first time living abroad and in a new country. Born in Kyoto, the former capital of Japan, feeling like an outsider was not a new emotion. Even in her homeland she felt isolated by her passions. Hiromi felt she did not fit in with all that was expected of her. Leaving Japan for America wasn’t going to give her a case of homesickness. She was already in a strong relationship with Roy, having known him for seven years prior to her relocation. They met when he was teaching English to Japanese high-schoolers. If you are wondering if Roy is fluent in Japanese, Hiromi notes,

She left Japan, and Jacksonville was her first time living abroad and in a new country. Born in Kyoto, the former capital of Japan, feeling like an outsider was not a new emotion. Even in her homeland she felt isolated by her passions. Hiromi felt she did not fit in with all that was expected of her. Leaving Japan for America wasn’t going to give her a case of homesickness. She was already in a strong relationship with Roy, having known him for seven years prior to her relocation. They met when he was teaching English to Japanese high-schoolers. If you are wondering if Roy is fluent in Japanese, Hiromi notes,

“He is almost none. My daughter and I can talk something bad in Japanese and he doesn’t know. But he can feel it.”

Hiromi, newly-married upon arriving in Jacksonville, was now ready to embark and leave behind some of the stricter perspectives and traditions that had been imposed on her simply for being born in Japan. In her youth she was into rock bands and counter-culture. It was while living in Japan she discovered the beautiful American imagery of tattoos. Japan is highly recognized as having some of the most traditionally-beautiful tattoo imagery in the world. Hiromi is not a traditionalist. She decided to become an apprentice, which was very taboo at the time. Most studios didn’t label them on the outside of the business, making it difficult to find and easy to stay hidden.

“If my neighbor saw me, saw this (pointing to her tattoos), it’s still me but she would be like ‘ooooh Hiroromi,’ to her I would be bad.”

Can you imagine being judged as ‘bad’ just for having a tattoo? Hiromi sees the unfairness of being judged by personal choice and even more so by one that you can’t control. For instance, the case of choosing skin color is nonexistent, yet people are judged solely because of it. Lucky for us Hiromi’s teacher was not in the best head space, “He was a drug addict.” With infrequent instruction she soon moved on from tattooing. Hiromi tried body-painting, and she did embroidery. A childhood book about paper-cuts beckoned back to her to take a stab at the medium. No training, no art class, no fear. She would take the delicate nature and details of all her artistic loves and combine them in flawless tangible tangles of paper.

Living In America

“I thought I would have all kind of friends, African Americans, Middle Easterners, Caucasians, but no. I didn’t know what was going on in real life until I got here.”

Hiromi was confused about the less-than-utopic society she had adopted. She didn’t deny her heritage and culture. Her daughter goes to Japanese school. A different view was represented to her of America from the Japanese media. The expectation was to be surrounded by other cultures that she could learn from. She then recounted a story about an African American community called The Hill, its existence shattered by gentrification. “Even 12 years ago I didn’t see black people walking down the sidewalks.” She was frustrated, and her husband helped to fill in the gaps. She focused on raising her daughter and didn’t think of herself as a professional artist. Art has its elitism. Normally an uneducated artist is thought of as an outsider; Hiromi defies another label. She hasn’t been branded – in fact it makes her talent that much more incredulous. Hiromi has yet to find a teacher to match her skill set. It might be why she is so experimental. She has tried all types of paper to find what works for her art medium.

“I just guessed with the paper, and the scissors, I tried all different kinds. First it was too thick, others too thin. I find that the paper I’m using right now works the best. I have to remember where I got it.”

Rolls of black and white paper sit in the corner of her bedroom studio. She is grateful that her art is being so well-received. Like most artists, she wants the best materials, but they can’t always be afforded. She hasn’t cultivated the talent that some mixed media artists around town have for being a refuse for art. There is a perception of perfection that works against type for Hiromi. Where she would be pleased to receive paper from her peers and even patrons, few would answer the call. She isn’t seeking donations, but a roll of paper wouldn’t be refused. Most outsiders could be fraught with worry that they would interfere with her process. Instead of leaning on others, Hiromi has learned to lean in to her usefulness, though she does accept the advice and experience of others to guide her to better options. When first displaying her paper-cuts she used a hanging material that was too heavy for the delicate paper. Her work, so stunning, when she first started exhibiting she used frames. It was pointed out to her that this took away from her art and the medium wasn’t able to be noticed as visually. Roy, also an excellent artist in carpentry, helped his wife discover that using small pins in her work would give the illusion of them being suspended, allowing the viewer to take in the paper-cut in its full glory. Even now, they experiment with installing Hiromi’s work. In LIFT: Contemporary Expressions of the African American Experience, the shadows of the 12 faces in her artwork were a “happy accident.”

In preparation for the works to be installed in the Jacobsen Gallery, the Cummer Museum installers and the artist herself thought the works would be very labor intensive. In the background they considered painting grey behind the silhouettes. However, after angling the lights, the shadows appeared, giving the works volume. “They perfectly fit the theme of the show.” She specifically chose white paper to express the black faces. The original drawings were drawn in black ink, but cutting white paper wasn’t without its challenges. “It was a little hard to see. But once up on the wall it came together effortlessly.”

In preparation for the works to be installed in the Jacobsen Gallery, the Cummer Museum installers and the artist herself thought the works would be very labor intensive. In the background they considered painting grey behind the silhouettes. However, after angling the lights, the shadows appeared, giving the works volume. “They perfectly fit the theme of the show.” She specifically chose white paper to express the black faces. The original drawings were drawn in black ink, but cutting white paper wasn’t without its challenges. “It was a little hard to see. But once up on the wall it came together effortlessly.”

It’s A Small World After All

It must be satisfying to no small degree that in LIFT, Hiromi is exhibiting with the very person who gave her the display advice, Professor Dustin Harewood. He also made a way for her into the arts arena of Jacksonville by giving her the opportunity to exhibit one of her first major shows. In this very house where I sit and drink coffee made by the Moneyhuns, Mr. Harewood came to see examples of Hiromi’s work. He became instantly smitten. She is also a fan of the Professor. An exquisite piece from his “coral reef” series hangs proudly in their living room. It is here that I too want to get to know Hiromi a bit better than I think I do. Though she does comment, “Shawana, you know me better than most.”

Hiromi is treated as if she was a unicorn – something to be in awe of, but elusive to touch or to get close. Hiromi’s face is beautiful but reserved. Her smile is big, but often she is caught with her lips pressed together. Her nod lets you know she is understanding of your point, and she often voices sounds over words when construing her position. Instead of a long horn, she dons a black uniform. The coolness of her constantly being in black causes mystification. It deceives you into forgetting that in a head filled with intricate details it’s just easier to not focus on her wardrobe. Those details are left to the art. They can be traced in the faces of Augusta Savage, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Shirley Chisholm, if you choose to get closer for a better view.

While standing behind a patron she overheard them discussing her work; someone even thought all the faces were the same. Tsk Tsk! Many can tell you how much they love Hiromi’s work but could not tell you whose faces are represented. It’s not lost on Hiromi that her work is highly praised but why was a Japanese woman chosen as an artist to be in this exhibition that is reverberated around race. Even she was confused. She took the invitation seriously and decided to do her own research. It was an education; she was unfamiliar not only with the song Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing but also of all the history.

“I know a few people would not want to step into the room, or even into a museum. That’s too bad for them. Now we can be there (at the Cummer Museum) or go there and just talk about it (racial issues).”

Her ignorance was not lost on her; she even began to educate her Japanese friends who live here. “They didn’t know. Not just about the racism but everything. Because of me being a part of the show, they learned a reality they didn’t know existed. A different part of Jacksonville. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe, but now I could see.”

Domo Aragato, Mr. Roboto

Though she can’t always get out of her efficient two-story beach house to come into the core neighborhoods. She enjoys the bikeability of living at the Beaches. The family that bikes together lives in a house once owned by her in-laws. She worked in her father-in-law’s embroidery shop before he passed and helped with the business before focusing solely on her burgeoning art career. Roy has used his mastery in carpentry to make his wife feel more comfortable. It’s unique, showing off both their characters with modern accents of Japanese furniture. At the time of this interview, Hiromi was getting ready to leave the beach bungalow for an exhibit at the Florida International University in the Phillip & Patricia Frost Museum in Miami, Pierce, Mark, Morph. This week all the cool kids are off to Miami for Art Basel. Miami has transformed itself. Only third behind Los Angeles and New York for artist stateside to get international exposure. This innovator has already been. Her group exhibition opened October 22. Jacksonville is trying to be the newest artist hub. LIFT has given the city national recognition.

Hiromi’s group exhibition will be still up for viewing during Art Basel. This could give her work a significant interest beyond the 904. Both group exhibitions coincidently come down in February; LIFT comes down on Lincoln’s Birthday, February 12.

Hiromi’s group exhibition will be still up for viewing during Art Basel. This could give her work a significant interest beyond the 904. Both group exhibitions coincidently come down in February; LIFT comes down on Lincoln’s Birthday, February 12.

Hiromi is back home and currently working on an untitled series. Women and architecture are the central themes. Hiromi’s style is evolving again. In Japan they have a saying, “Ganbatte,” it means, do your best! Currently 39 years of age, Hiromi is unwilling and unsatisfied to do just do her best – “I want to do better.”

You have done it again girlfriend. Great write.

Thank you Marsha!

[…] might be why Dustin Harewood admires fellow LIFT artist Hiromi Moneyhun. Dustin and Hiromi have a lot of connections beyond art, of course the most superficial being she is […]