Written by Shawana Brooks, Guest Contributor

Ducasse Overstreet and Shawana Brooks

They Are Leaving On A Jet Plane

Overstreet Ducasse is going places. Literally. Before settling in to conduct this interview, his upcoming trip to Bristol, England is consuming most of his attention. He fields phone calls from collectors and other concerned parties. His feet glide with the confidence of artistic ownership across the canvas in his extended studio… unable to contain his genius to his 12 x 12, which is completely covered in pieces of antiquities, frames, and scraps that only Ducasse can identify. It’s in this mixed media artist’s treasure trove – a mixture of dumpster diving, collectables, and good-natured friends endorsing use of their ex-valuables – that Street (his more familiar name) will create his signature art. He’s in the process of creating two new works to take to England. Their subject matter, the current politicizing of gender subscription and referendums on bathrooms. It’s tricky material, and Ducasse himself admits, “It’s the first time I created a piece, and I’m like ‘oh my god, I’m 50/50 on this one’.”

That is the pinnacle for what Ducasse’s work normally does for viewers. Pushes them to re-examine their ideals and beliefs. In this case its him being pushed, and he’s delighted. His face thwarted by pensiveness, examining the piece on the floor. It’s an unspoken rule of acceptance in Labs (CoRK Arts District, East Building) that if an artist is in their mode, they can create as they need. Street is in need, as he spills over into the common area next to his studio. One of the four artists he currently shares with is Roosevelt Watson III, fellow LIFT exhibitionist and DEEPressionist member, a movement Ducasse, Watson, and visual artist Adrian Rhodes started, to help define the state of arts and culture in Jacksonville around 2004. The name gives it away a bit, and Ducasse is still heavily attached to it, and little less to the group, as each is making a respective name for himself. He swiftly ends the phone conversations to dive back into dialogue with other studio mate, international artist Zac Freeman. He’s deep in deliverance with tales of his good fortune to go on this residency/exhibition, in part sponsored by the Cultural Council of Greater Jacksonville. I wait to hear his catchphrase “I’m serious”, one that if you are familiar with his vernacular, cognates your attention. He wants you to understand this is no mistake, he is not being rewarded, and this is the result of years of hard work. I listen to his plan of attack. Ducasse is not worried on the surface. His infectious laugh and bravado relish the opportunity to make his debut. Thriving on pressure, deadlines are still his bigger motivator and foe. He readily admits to not always being able to paint for the sake of making a mark. He pushed himself and others to these limits just a few months ago, turning in his artwork, “Protect Ya Neck” to the Cummer Museum, mere days before the opening of LIFT: Contemporary Expressions of the African American Experience. Instead of turning it away, the Museum made room for it. Why would they do this for Overstreet? He proven he’s worth the angst.

That is the pinnacle for what Ducasse’s work normally does for viewers. Pushes them to re-examine their ideals and beliefs. In this case its him being pushed, and he’s delighted. His face thwarted by pensiveness, examining the piece on the floor. It’s an unspoken rule of acceptance in Labs (CoRK Arts District, East Building) that if an artist is in their mode, they can create as they need. Street is in need, as he spills over into the common area next to his studio. One of the four artists he currently shares with is Roosevelt Watson III, fellow LIFT exhibitionist and DEEPressionist member, a movement Ducasse, Watson, and visual artist Adrian Rhodes started, to help define the state of arts and culture in Jacksonville around 2004. The name gives it away a bit, and Ducasse is still heavily attached to it, and little less to the group, as each is making a respective name for himself. He swiftly ends the phone conversations to dive back into dialogue with other studio mate, international artist Zac Freeman. He’s deep in deliverance with tales of his good fortune to go on this residency/exhibition, in part sponsored by the Cultural Council of Greater Jacksonville. I wait to hear his catchphrase “I’m serious”, one that if you are familiar with his vernacular, cognates your attention. He wants you to understand this is no mistake, he is not being rewarded, and this is the result of years of hard work. I listen to his plan of attack. Ducasse is not worried on the surface. His infectious laugh and bravado relish the opportunity to make his debut. Thriving on pressure, deadlines are still his bigger motivator and foe. He readily admits to not always being able to paint for the sake of making a mark. He pushed himself and others to these limits just a few months ago, turning in his artwork, “Protect Ya Neck” to the Cummer Museum, mere days before the opening of LIFT: Contemporary Expressions of the African American Experience. Instead of turning it away, the Museum made room for it. Why would they do this for Overstreet? He proven he’s worth the angst.

Take It From Me……Patrons Just Don’t Understand

The Work of Art

If deadlines can be his antithesis, he is also fiercely motivated by competition. Ducasse is unsure, but has heard that street artist, Banksy, is the current artist on exhibition at the Cultural Center in Bristol. If Banksy is not directly exhibiting at the Cultural Center he does have a direct connection to our sister city. They have crafted an award-winning walking tour of his murals and celebrate his humble beginnings. Bristol can teach our cultural leaders a thing or two about celebrating their homegrown talent. Banksy’s identity is still well hidden, and Ducasse is hyper aware what displaying his work in an international gallery means on his resume. The bar is set high.

The confidence of showing in a reputable museum, such as the Cummer Museum, in his adopted city of Jacksonville has given him new resolve. He jokes “If there was anyone to choose” referring to him being a key player in the success of this exhibition.

It’s true, Overstreet has become synonymous with art excellence in a way that many black artists in Jacksonville envy, which is the stigma of being a “black artist.” This is no dalliance to Overstreet. He doesn’t try to present his art outside the color lines. But he doesn’t actively base his artistic decisions on them. Though he identifies as an African American, he knows his perspective is one of an immigrant. He also has a difficult time with African Americans not being celebrated directly.

This isn’t the first time he’s exhibited in the Cummer Museum; he stole the show in Jefree Shalev’s Our Shared Past. He was especially sought after to participate. He’s aware of why those opportunities are afforded to him. Being the first isn’t always glamorous, but he knows he hasn’t had to do that in LIFT. The exhibition is historic in many different ways, and Ducasse isn’t the only stand-out. He remarks that this is one of the best exhibitions he has been in thus far in his life. “Everyone brought their ‘A’ game.”

When asked about a favorite artist or a piece in the Jacobsen Gallery besides his own, he sits back on the couch and takes a few minutes before replying. People gravitate towards Overstreet’s criticisms. His voice can be the dissenting one in a room of co-conspirators. He starts to gush over the realization that he is exhibiting with a former classmate, Thony Auippy, and his former professor, Dustin Harewood. He gets emotional. All the LIFT artists have interesting connections to each other.

“Thony for some reason has left a mark in my heart. There is something about his soul that you can feel, he is a genuine dude. But I’ve never been a fan of his ART, until now. I’ve found canvases in the trash (at CoRK) with his name on it. Now I love his work. His art takes it to the next level. It was powerful for me to stand in front of it,” says Ducasse.

This is thematic for many of the artists in LIFT.

Oooh Baby I Like it Raw

Studio Stuff

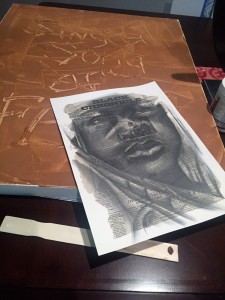

Overstreet has been feeling the call for the next level for years and has made the most out of every opportunity afforded, “You can’t count nothing out.” He paces the wooden floors looking at the work on the ground and speaks of how he loves this time. Process. He feels like an hour glass; his demeanor resembles one too. Standing in a T-shirt of his own design and the traditional American artist garb of painted lived-in jeans. Overstreet is leaving in a few days and obviously wants his best work with him for display.

It was in 11th grade when the young artist overheard people looking at his award-winning art. At the time, he was focused on drawing hyper-realistic figures. Unknown to them, he heard two dissenting critiques to the work. “It was so photo realistic, some people thought it was amazing, the best they ever saw. The other was so what? He just took a picture, anybody can do that,” he started to think outside of the expression on his subject’s face.

“What was I drawing? It was definitely a process to try and figure out how am I going to exhibit what I’m thinking versus using images from other people to exhibit what I’m thinking.”

He figured out a way to marry the figurative to the expressionist. He also transferred from paper and pencil to found objects and acrylics, mixed media.

Now with just a few days to get it all together, Street is slightly worn. It reeks and parallels problems that Augusta Savage had with preserving her work for the 1939 World’s Fair. Savage was offered several opportunities as an artist. They were either revoked once knowing her racial background, or she was unable to participate because of her socio-economic situation.

Overstreet is suffering from the latter. The thin budget for this sizable opportunity has caused him to seek fundraising in support of his trip. Had he already had the funds for proper shipping, he might be enjoying these few days for packing. Instead, he’s diligently trying to pull out MAGIC that he should keep on reserve. Either the community will step up with funding for Overstreet Ducasse to present the best of himself, or he will be forced to manifest two new paintings to fill up that space. So many times this is the case for artists here. Either they must leave to be appreciated, or they stay and suffer the lack of direct sponsorship. At least Overstreet has the advantage of being popular in the community he serves and might not have to create these two paintings after all.

Man In The Mirror

LIFT continues to play a significant role in the theater that is arts and culture in Jacksonville. Overstreet is unbothered by our local color. A recent creative sabbatical to upstate New York gave way to discomfort. Riding in scenic Philadelphia made him long for the occasion of being hurled an obscenity during the late, late nights of his neighborhood of Riverside. Overstreet makes his peace with those incidents. Since his arrival in the U.S., he’s lived mostly in Florida, with some time in California. Still new to exploring America, the proud Haitian was not prepared for the racial division that he witnessed. Though Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing’s lyricism and James Weldon Johnson were not integral to his existence as a young man, they have had their place artistically. Over the years of exhibiting in Black-themed shows, like the annual Through Our Eyes exhibit at Ritz Theatre & Museum, where he was first recognized as a professional artist here in Jacksonville, Ducasse was already aware of James Weldon Johnson from past research. He deliberately stepped away from the lyrics of Lift or his personal inspiration and focused on music itself.

“Hip-Hop is more influential than any art class I took in my life.”

“Racism”

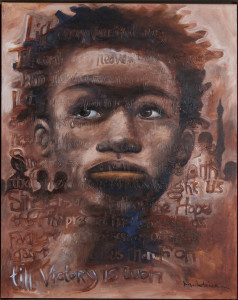

He is subconsciously listening to a soundtrack for his trip, the Beatles playing on a loop in the background. Earlier, Street was listening to fellow travel-mate Mal Jones, something he’s done for years. Again, no accident he feels they are going on this trip together. He’s used music, and in works of art he’s created for this exhibit, like my favorite “Racism”, he explores words and their meaning, asking viewers to look at RACE I AM and RACE IS HIM.

Overstreet does not think art should be high brow. “We all have blindspots, no one is perfect.” He wants you to connect to his art, in fact he demands it. The high-functioning introvert, though slightly now more known, still hides in plain sight amongst viewers looking at his work. Overstreet mentions his favorite thing, besides all the amazing programming for LIFT, is talking to visitors of the Museum.

“Art should not be intimidating. It should not just suit the elite. I like to talk about the work. I’m much more comfortable doing that than just talking about myself. There is no fear to that.”

I have seen it with my own eyes. People clamoring over the work with the artist directly behind them listening or waiting to join. Their surprise that the picture on the wall (of the Artist) is in direct conversation with them now. Attending a TEDx Panel on (Re)Defining Art brought up a statistic that over 90% of people appreciate art but only 29% revere artists. Tssk Tssk. The National Endowment for The Arts released a statistic in 2013 that artists represent 1.4% of the labor force, but they have an outsized role as entrepreneurs and innovators who contribute to the vitality of the communities where they LIVE and WORK.

The Jacksonville community has changed in the three months this exhibition has been up, and Overstreet is changing too. The life-long animal aversionist recently conquered his fear by adopting a three-legged cat. He ponders his growth in now finding joy in a creature who’s happy to see him. How silly he was to fear animals for 40 years. He’s happy knowing that kindness. “I’m growing!” he spits jollily. We remark how empathy has a way to do that. How art does that!

“If you can fear anything, don’t let them make you fear art.”

Art can be fearful. It represents a truth that this life is not the same for everyone, sometimes for no fearful reason at all. The fact that this reality exists and needs to be validated is scary. Scary to know that now we are seeing this truth through art in a place that is safe and comforting. Frightening. For what can we do to make sure this art has a stronger presence and doesn’t get destroyed for lack of conservation and support of the artists who create it? It would be Savage if this happened. On the 23rd of this month we send one of our best off to go find success across international waters. The British aren’t looking their best with Brexit. I’m sure Overstreet will bring back a tale or two of fortuitous destiny.

The Rooms Where it Happens

The Rooms Where it Happens

At the time of this interview, Thony was getting ready for two shows, one solo. In the exhibition Till We Have Faces at the Karpeles Manuscript Museum, he will be revisiting more than 50 of his paintings. The other is a group show, A More Perfect Union: Explorations for Human Rights, which opened February 3 at the Space Gallery. Thony loves the idea of displaying art close to home. A mixture of southern landscapes, plantation houses, drawings, and his Worker series will line the walls of the Karpeles, while in A More Perfect Union, he will be reunited in displaying art with fellow LIFT artists

At the time of this interview, Thony was getting ready for two shows, one solo. In the exhibition Till We Have Faces at the Karpeles Manuscript Museum, he will be revisiting more than 50 of his paintings. The other is a group show, A More Perfect Union: Explorations for Human Rights, which opened February 3 at the Space Gallery. Thony loves the idea of displaying art close to home. A mixture of southern landscapes, plantation houses, drawings, and his Worker series will line the walls of the Karpeles, while in A More Perfect Union, he will be reunited in displaying art with fellow LIFT artists

You can see that in the work in LIFT, particularly in the piece Stony the Road. It was at one of those “hustling” exhibitions where then Cummer Museum Director Hope McMath gave him the beginnings of what LIFT would be. She vocalized her intention for his work to be a part of the exhibition. Maybe that is why Thony was one of the first artists to fully complete his work. At the shared meeting of participating artists, all were dumbstruck around the room when he voiced he was finished. Most of the artists were in the middle of their works, and one had not even begun.

You can see that in the work in LIFT, particularly in the piece Stony the Road. It was at one of those “hustling” exhibitions where then Cummer Museum Director Hope McMath gave him the beginnings of what LIFT would be. She vocalized her intention for his work to be a part of the exhibition. Maybe that is why Thony was one of the first artists to fully complete his work. At the shared meeting of participating artists, all were dumbstruck around the room when he voiced he was finished. Most of the artists were in the middle of their works, and one had not even begun.

Go across the pond and you will find the name Harewood in a grand abundance. Here in Jacksonville, there is only one that is on everyone’s lips at this moment, Professor Dustin Harewood. The name is getting much notice, and his art is a standout around our city. Murals line walls in

Go across the pond and you will find the name Harewood in a grand abundance. Here in Jacksonville, there is only one that is on everyone’s lips at this moment, Professor Dustin Harewood. The name is getting much notice, and his art is a standout around our city. Murals line walls in

That is exciting. Several artists throughout history received more fame and recognition as they got older just like one of Dustin’s art heroes, Gerhard Richter. “Artists who take the time to mature have a different quality to what they’re making than a prodigy; it can be a mixed blessing to get too many accolades too early.”

That is exciting. Several artists throughout history received more fame and recognition as they got older just like one of Dustin’s art heroes, Gerhard Richter. “Artists who take the time to mature have a different quality to what they’re making than a prodigy; it can be a mixed blessing to get too many accolades too early.” Nina turned her art into activism in a very less than subtle way during her heyday, but you would have to know who she is to enjoy the subtlety in Harewood’s artwork. “There shouldn’t be a novelty to exhibiting. We have to be interesting as contemporary artists period. Or you will unwillingly brand yourself as such.” A sample from Kanye West’s, “Blood On the Leaves” is what reminded him of the depth of Nina’s lyricism. “I didn’t start off thinking of Nina, and I didn’t want go to images like Billie Holiday. I was a little apprehensive.” The chills he felt when he heard her voice solidified his choice. Nina’s commitment to unapologetic blackness interfered with her artistic success, something that can be parlayed on to contemporary black artists of today. To be

Nina turned her art into activism in a very less than subtle way during her heyday, but you would have to know who she is to enjoy the subtlety in Harewood’s artwork. “There shouldn’t be a novelty to exhibiting. We have to be interesting as contemporary artists period. Or you will unwillingly brand yourself as such.” A sample from Kanye West’s, “Blood On the Leaves” is what reminded him of the depth of Nina’s lyricism. “I didn’t start off thinking of Nina, and I didn’t want go to images like Billie Holiday. I was a little apprehensive.” The chills he felt when he heard her voice solidified his choice. Nina’s commitment to unapologetic blackness interfered with her artistic success, something that can be parlayed on to contemporary black artists of today. To be

Somewhere, Over In Mandarin

Somewhere, Over In Mandarin Marsha didn’t exhibit again professionally until Through Our Eyes. At the time its home was at channel 7, not yet at the infamous

Marsha didn’t exhibit again professionally until Through Our Eyes. At the time its home was at channel 7, not yet at the infamous

Towards the right of the table sits imagery similar to LIFT. Faces of black-skinned boys and girls seep through copies of a newspaper past its prime, The Black Chronicle. She shares the complexity of the supposed easy task. Its evolve-ment disgruntles her personal process. “It’s not always a good thing. It doesn’t stop (ideas). I can keep on.” The usual low lull in her voice is replaced by squeaks of admonishment. “Though I never know when to stop.” Her southern drawl is laced with artistic discovery. Hatcher is proud of the work she completed for LIFT; of the thousands of pieces she’s done in her lifetime these are in her top ten percent. Artists are all fairly hard on themselves and don’t always think their work has hit the mark. She is inspired by artists like Elizabeth Catlett and Augusta Savage, and her fellow LIFT artists too. In reference to the exhibition she says, “I think its exceptional (LIFT). It’s edgy and its controversial, but it’s relevant.”

Towards the right of the table sits imagery similar to LIFT. Faces of black-skinned boys and girls seep through copies of a newspaper past its prime, The Black Chronicle. She shares the complexity of the supposed easy task. Its evolve-ment disgruntles her personal process. “It’s not always a good thing. It doesn’t stop (ideas). I can keep on.” The usual low lull in her voice is replaced by squeaks of admonishment. “Though I never know when to stop.” Her southern drawl is laced with artistic discovery. Hatcher is proud of the work she completed for LIFT; of the thousands of pieces she’s done in her lifetime these are in her top ten percent. Artists are all fairly hard on themselves and don’t always think their work has hit the mark. She is inspired by artists like Elizabeth Catlett and Augusta Savage, and her fellow LIFT artists too. In reference to the exhibition she says, “I think its exceptional (LIFT). It’s edgy and its controversial, but it’s relevant.”