Indigo cakes

On the east wall of the Mason Gallery an untitled fashion piece by Gary Graham is described as follows; Coat: wool and cotton engineered Jacquard; Leggings: digitally printed cotton twill and Lycra. This coat was made with indigo dye. When studying the extraction steps of indigo dye from its plant, Indigofera tinctoria, we learned that the extract might also contain a red dye called indirubin.

On the east wall of the Mason Gallery an untitled fashion piece by Gary Graham is described as follows; Coat: wool and cotton engineered Jacquard; Leggings: digitally printed cotton twill and Lycra. This coat was made with indigo dye. When studying the extraction steps of indigo dye from its plant, Indigofera tinctoria, we learned that the extract might also contain a red dye called indirubin.

Indirubin

Curious about indirubin’s color and properties I learned that indirubin is an isomer of indigo (indigotin). That is, indirubin and indigo have the same chemical components but different structural arrangements. (As an analogy: Take the letter components a, e, b, r and from that make the isomers bare and bear or the components o, p, t and make the isomers pot and top.) The result is that each isomer has different properties; for one, indigo is blue and indirubin is red.

Besides being a dye, on its website, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has a list of purported uses for indirubin that includes treating cancer (supported by non-human animal studies), reducing inflammation, and treating psoriasis. In addition, articles reveal that many laboratories are producing indigo and indirubin with recombinant E. coli.

Besides being a dye, on its website, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has a list of purported uses for indirubin that includes treating cancer (supported by non-human animal studies), reducing inflammation, and treating psoriasis. In addition, articles reveal that many laboratories are producing indigo and indirubin with recombinant E. coli.

Bacteria of the human gut also produce the precursors to indigo and indirubin. Intestinal bacteria degrade trytophan into indole, some of which converts into indoxyl molecules, which leave the body in the urine. In the indigo fermentation vessels, the extracted indoxyl molecules oxidize to make the indigo pigment. Certain abnormal conditions, such as Purple Urine Bag Syndrome or PUBS, will cause the production of indigo and its isomers within the body. Excreted, the blue indigo and red indirubin cause the urine to be purple (art note: red + blue = purple).

“Mad” King George

My curiosity led me to discover that purple urine, coupled with urinary tract infections and chronic constipation, have led historians to speculate, that amongst his other ailments, King George III of England (“Mad” King George ruled 1760 to 1820) had PUBS. Even th ough, being tagged as “mad” to the world and a “tyrant” in the Colonies, history does attribute him with some redeeming qualities. King George III showed great interest in science and mathematics, not only by collecting technology of the time, but also, by funding scientific endeavors. Historians say that the advancements of agriculture during his reign laid the foundations of the industrial revolution.

ough, being tagged as “mad” to the world and a “tyrant” in the Colonies, history does attribute him with some redeeming qualities. King George III showed great interest in science and mathematics, not only by collecting technology of the time, but also, by funding scientific endeavors. Historians say that the advancements of agriculture during his reign laid the foundations of the industrial revolution.

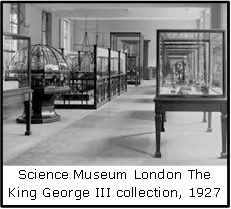

A revo lution that included the establishment of large textile mills with its new technology – innovations collected from all over. One such new technology was the Jacquard loom, named for Joseph Marie Jacquard, a French weaver and inventor. Perhaps, not so much new technology as an aggregation of previous innovations, Jacquard in 1801 introduced a mechanism that automated the creation of intricate patterns produced on a loom. (Jacquard can refer not only to the mechanism but also to a fabric of intricate weave, hence, a coat of wool and cotton-engineered Jacquard.)

lution that included the establishment of large textile mills with its new technology – innovations collected from all over. One such new technology was the Jacquard loom, named for Joseph Marie Jacquard, a French weaver and inventor. Perhaps, not so much new technology as an aggregation of previous innovations, Jacquard in 1801 introduced a mechanism that automated the creation of intricate patterns produced on a loom. (Jacquard can refer not only to the mechanism but also to a fabric of intricate weave, hence, a coat of wool and cotton-engineered Jacquard.)

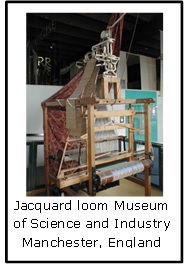

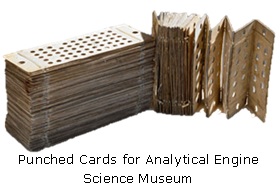

Jacquard punch cards

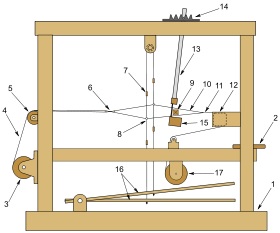

Based on a series of punch cards strung together by rope, a pattern could be “stored” and be used to produce the same pattern again and again. The Jacquard loom is recognized as a great innovation not only for what it did for the textile industry, but also for what it contributed to further technological advances in fields like computer sciences.

However, before we satisfy our curiosity about the connection to computers, I found it interesting on how the punch cards of the Jacquard loom functioned. First, we need a little weaving lesson – I will attempt to keep the weaving jargon to a minimum, for as I read through it, I began to feel a little bit like King George on a bad day myself.

However, before we satisfy our curiosity about the connection to computers, I found it interesting on how the punch cards of the Jacquard loom functioned. First, we need a little weaving lesson – I will attempt to keep the weaving jargon to a minimum, for as I read through it, I began to feel a little bit like King George on a bad day myself.

Cuboid loom

Star Trek warp lines

Picture yourself sitting in front of a rectangular cuboid with the length going away from you – let’s call this structure your loom. A bunch of threads are attached the length of this structure (all together they are called the warp, a single thread is called a warp end or end – think Star Trek and the speed lines that indicated the ship going into warp.). The weft is the thread that goes perpendicular to the warp. Lifting warp ends allows the weft to pass underneath some ends and over others, making a weave. Heddles lift the ends; one warp end passes through one heddle. The heddles are in a row, vertically perpendicular to the warp and attached to a lifting shaft at the top of your loom.

Now, if you put a roof on your loom, the heddles’ upward movement stops and none of the warp ends lift up. However, if you made some holes in the roof, the heddles would be able to rise wherever there was a hole, once again lifting the ends. Finally, carefully place the holes in the roof in rows and move the roof towards you a bit at a time. The heddles and the ends will then lift automatically in a prescribed manner. Sending the weft across each time ends lift up in response to heddles passing upward through a row of holes results in one more line of the pattern in your fabric. This ‘holey’ roof is the punch cards of the Jacquard; it is the memory of the pattern and the tool of production. Today, computer software controls the movement of the heddles.

Now, if you put a roof on your loom, the heddles’ upward movement stops and none of the warp ends lift up. However, if you made some holes in the roof, the heddles would be able to rise wherever there was a hole, once again lifting the ends. Finally, carefully place the holes in the roof in rows and move the roof towards you a bit at a time. The heddles and the ends will then lift automatically in a prescribed manner. Sending the weft across each time ends lift up in response to heddles passing upward through a row of holes results in one more line of the pattern in your fabric. This ‘holey’ roof is the punch cards of the Jacquard; it is the memory of the pattern and the tool of production. Today, computer software controls the movement of the heddles.

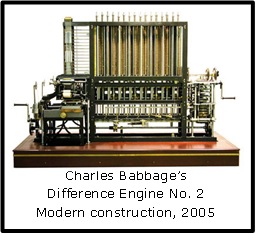

It seems fitting that the progeny of Joseph Marie Jacquard’s punch cards control the textile looms of today. In the mid 1800s Charles Babbage, an English mathematician, gained inspiration from Jacquard’s punch cards. Working on mechanical methods to create more accurate marine

It seems fitting that the progeny of Joseph Marie Jacquard’s punch cards control the textile looms of today. In the mid 1800s Charles Babbage, an English mathematician, gained inspiration from Jacquard’s punch cards. Working on mechanical methods to create more accurate marine  navigation tables, he saw the potential that the cards could also store abstract calculations. In recognition to the Jacquard loom, Babbage used two weaving industry terms, the ‘Store’ and the “Mill”, to name parts of one of his calculating mechanisms. The Store held numbers and the Mill was where the numbers were “woven” into new results. Today we call this the memory unit and the central processing unit (CPU).

navigation tables, he saw the potential that the cards could also store abstract calculations. In recognition to the Jacquard loom, Babbage used two weaving industry terms, the ‘Store’ and the “Mill”, to name parts of one of his calculating mechanisms. The Store held numbers and the Mill was where the numbers were “woven” into new results. Today we call this the memory unit and the central processing unit (CPU).

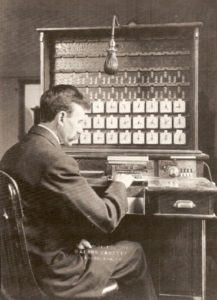

Herman Hollerith, an American inventor, took another step; unaware of Babbage’s proposal that punch cards could not only store original calculations but also produce and store new calculations, he perfected a system that today we might call read/write technology. Answering a challenge from the U.S. Census and winning a prize in doing so, the Hollerith Desk read cards and calculated data automatically for the 1890 census. His invention allowed for the completion of the census in three years (it took 7.5 years for the 1880 census to be completed) and saved $5 million as well. From his success, Hollerith built a company, the Tabulating Machine Company that eventually became IBM. Punch cards soon were everywhere and became synonymous with the computer age.

Herman Hollerith, an American inventor, took another step; unaware of Babbage’s proposal that punch cards could not only store original calculations but also produce and store new calculations, he perfected a system that today we might call read/write technology. Answering a challenge from the U.S. Census and winning a prize in doing so, the Hollerith Desk read cards and calculated data automatically for the 1890 census. His invention allowed for the completion of the census in three years (it took 7.5 years for the 1880 census to be completed) and saved $5 million as well. From his success, Hollerith built a company, the Tabulating Machine Company that eventually became IBM. Punch cards soon were everywhere and became synonymous with the computer age.

Nearly one hundred years later the Jacquard loom is still in use, guided now not by punch cards but by computer software. In this case, Pointcarre Textile Software guided the weave of Gary Graham’s fabrics.

Pointcarre Software

Curious about the software’s name, coupled with some misdirected Googling, I inquired with the software company if the name had anything to do with French mathematician Henri’ Poincare. In a way it did; my answer came from the President of Pointcarre USA:

“Henri Poincaré was a strong influence on Olivier Masson, the originator of the Textile Software and a Mathematician and Weaver in France. He also changed the term to mean “Square-Dot” which is a pixel on the screen, as in our software.”

Henri Poincaré

Henri Poincaré contributed to the many branches of mathematics, but much of his work based around his curiosity and ‘contemplation of mathematical spaces in which several coordinates determine the position of a point’. I can see how a weaver would find inspiration and a software creator would find direction from this to create a design. Poincaré, also has been tagged with the reputation as a polymath, a person who has expertise in many fields, a person who can draw on knowledge from many fields to solve a specific.

Look at the east wall of the Mason Gallery; there are a multitude of fields represented here. Represented are years of knowledge drawn from science, math, and technological invention. There are years of history and societal experience. There is curiosity. There is art.

Folk Couture: Fashion and Folk Art will be on display until December 31, 2016.