In the 19th century, passenger pigeons numbered nearly 4 billion individuals. Massive hunting and habitat destruction were the main causes of the species’ demise. “Martha,” the last passenger pigeon, died in captivity on September 1, 1914. Image from Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Extinction is defined by Merriam-Webster as the condition or fact of being extinct or extinguished; no longer existing. There are many species of plants and animals that have become extinct, and many more are expected to become extinct. Gone from our planet. Forever. Think about that.

The Carolina parakeet was the only parrot species native to the eastern United States. Its forest habitats were removed to make space for agriculture, and they were hunted heavily to provide feathers for ladies’ hats. The last captive Carolina parakeet died in captivity on February 21, 1918. Painting by John James Audubon

Even though extinction is a naturally occurring phenomenon, the normal “background rate” for the loss of species is one to five per year. Unfortunately, scientists predict that we are currently losing plants and animals at a rate of 1,000 to 10,000 times the background rate, translating to dozens being lost every day, and we could see many as 30 to 50% of our species head toward extinction by the middle of this century. This crisis is almost entirely due to the actions of mankind, through the loss of habitat, the introduction of species not normally part of a landscape, environmental pollution, the spread of disease, and climate change.

‘The Lost Bird Project’ on display at McCall City Park, Portland, Oregon in 2010. Photo from toddmcgrain.com

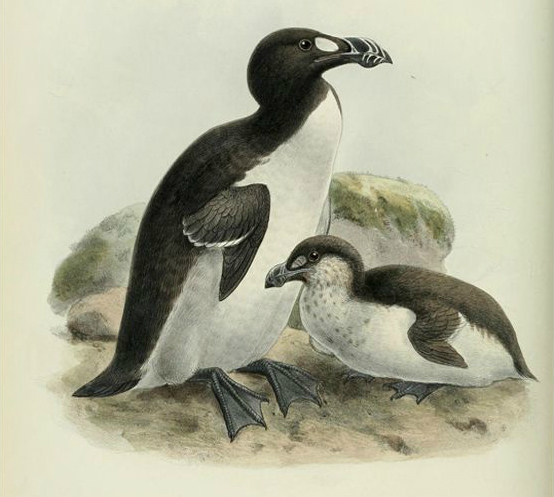

Todd McGrain: The Lost Bird Project is an exhibition on view in the Museum’s J. Wayne and Delores Barr Weaver Community Sculpture Garden & Plaza through October 21, 2018. The exhibition features five large-scale sculptures and is supplemented by the presentation of preparatory drawings in the Bank of America Concourse, a gallery inside the Museum. As a chronicle of humankind’s impact on our changing world — excessive hunting and fishing, commerce, deforestation — and a record of dwindling biodiversity (the variety of life), The Lost Bird Project memorializes North American birds that have been driven to extinction. The great auk, Labrador duck, passenger pigeon, Carolina parakeet, and heath hen were birds that once filled unique niches in the North American landscape from the shores of Labrador and New York to the Midwestern plains. Moved by their stories, American artist Todd McGrain (b. 1961) set out to bring their vanished forms back into the world. More importantly, these sculptures ask us not to forget, and remind us of our duty to save fragile habitats and prevent further extinction.

The heath hen lived in abundance along the Atlantic Seaboard from Massachusetts to Virginia. Because of overharvest and habitat destruction, by the mid-1800s there was only a single population left on Martha’s Vineyard. Despite efforts to save the species, the last bird was seen there in 1932. Photo courtesy of The Vineyard Gazette

The species on earth don’t live in a vacuum, and it is not known how the loss of one species will affect the other species within its ecosystem, but it is known that the removal of just one species from an ecosystem can set off a chain reaction among all the remaining plants and animals. This, in turn, negatively affects the natural processes or the species composition of the ecosystem. But why should we care? What do all these species mean to humans, anyway?

The great auk was plentiful until the mid-16th century, when European sailors began the exploration of the oceans. Over-harvest of eggs, meat, feathers, fat, and oil was the main reason for its extinction. Painting courtesy of Smithsonian Magazine

Many advances in medicine have come from plants and animals; more than a quarter of U.S. prescriptions written each year contain chemicals originally discovered in them. About half of currently available medicines have been derived from a few hundred wild species, including antibiotics, cancer treatments, pain killers, and blood thinners. Every living thing on earth has its very own genetic makeup and biochemistry that has been evolving since they first came into being. Only a small number of species have been examined, and scientists have just begun to unravel their secrets to find benefits to humans. If we lose any single species, that information is gone forever, and that information could have been a treatment or cure for a human disease.

In the field of agriculture, farmers are using insects and other animals, such as bats, that eat pests detrimental to food crops. Plants with natural toxins are being used to repel some of these pests. In most cases these alternatives to synthetic chemical pesticides are less expensive and safer to use, both for the environment and for the people (including consumers) who interact with the crops.

The Florida scrub-jay is listed as a threatened species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Scrub habitat is highly valued for development, and habitat destruction and suppression of fire in the species’ remaining range are the main threats to its existence. There are just over 5,000 Florida scrub-jays remaining. Photo by James Lyon

Many individual plants and animals are indicators of the quality of the environment. When the number of peregrine falcons and bald eagles declined in the middle of the 20th century, scientists discovered that a common pesticide, DDT, was the cause. Eastern white pine and some lichens serve as indicators of extra sulfur dioxide, ozone, and other air pollutants. A decline in the number of freshwater mussels can indicate water pollution upstream from where they live. The Florida scrub-jay is an indicator species for the scrub ecosystem. When their numbers decline, so do those of the many other species of plants and animals that occupy the scrub habitat.

Plants are being used to remove, stabilize, transfer, and destroy pollutants that are found in the substrate in which they grow, be it soil or sediment. In this new field of study, called phytoremediation, plants remove heavy metals from soil and concentrate them in their stems, which are then harvested and disposed of properly. Some houseplants can remove indoor pollutants from the air in your home as well.

Ecotourism, through activities such as birdwatching, hiking, canoeing, camping, and kayaking add billions of dollars to the economies of countries around the world. Without the natural beauty of the environment, such tourism would diminish, damaging many economies.

These benefits are just a handful of reasons why plants and animals and their habitats should be protected. There are others, like flooding reduction, protecting pollinators for our crops and natural vegetation, buffering land against the impact of storms, and preservation of soil fertility. Many people believe that every life form should be protected simply for its intrinsic value, and that they should be left for future generations because they have been here on earth for so long. Some have compared eliminating entire species to ripping pages out of books that have not yet been read. As species are lost, so are options for the advancement of future generations, our children, our grandchildren, and all who follow behind us. We should, as humans, not be so selfish as to rob the future world of a cure for cancer or other devastating disease. Or rob the world of something that is simply unique. Extinction is forever.

Overharvest of the Labrador duck (or pied duck) and eggs on breeding grounds and habitat destruction following the arrival of Europeans were factors in the species’ extinction. It was last seen in 1875 in Long Island. Painting by John James Audubon

Sources:

Center for Biological Diversity. The Extinction Crisis. biologicaldiversity.org

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds. Can We Learn From The History Of The Heath Hen? allaboutbirds.org/can-we-learn-from-the-history-of-the-heath-hen/

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds. Even Small, Scattered Florida Scrub-Jay Groups Are Vital To The Survival Of The Species. allaboutbirds.org/even-small-scattered-florida-scrub-jay-groups-are-vital-to-the-survival-of-the-species/

Endangered Species International. Overview – Why Save Endangered Species? endangeredspeciesinternational.org/overview4.html

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Camptorhynchus labradorius (Labrador Duck). iucnredlist.org/details/22680418/0

John James Audubon Center at Mill Grove. The Last Carolina Parakeet. johnjames.audubon.org/last-carolina-parakeet

Smithsonianmag.com. When the Last of the Great Auks Died, It Was by the Crush of a Fisherman’s Boot.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Why Save Endangered Species? July 2005. endangered.fws.gov/